As I begin another semester of teaching, I wanted to share one thing I’m trying this time to improve attendance: peer instruction. We’ll see how it pans out!

Table of Contents

Attendance History

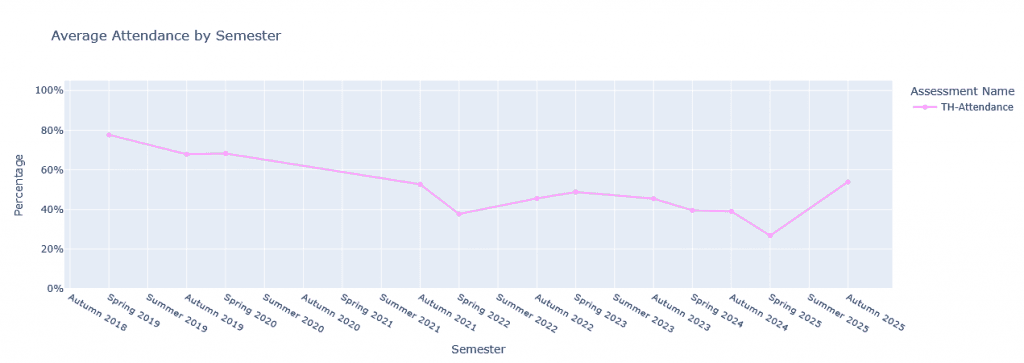

If you read my reflection last semester, you might have heard that I’m struggling a bit to get attendance. This didn’t used to be a problem, and it only has gotten worse in the last few semesters. Though, I suppose I should actually plot that out as a sanity check. Surprisingly, I’m not just imagining things:

According to this figure, the most attendance I’ve ever gotten was back in Spring 2019 when students attended about 78% of the time on average. Since then, I reached a horrific low of 27% in Spring 2025. Mentally, that’s like half the class showing up to the lectures and a tenth of them showing up to the labs, which lines up with my experience.

What’s encouraging is that I actually had a massive uptick in attendance this past semester at about 54%. Unfortunately, I don’t really know what I did differently, or if I had any real impact on attendance levels. I will say that some of the sections were able to build up some community, so that felt nice.

Because I can’t really know why attendance seems back up, I’m going to treat it like a fluke. And even then, attendance could still be a lot better. So, the question becomes: how do I sustain and even improve attendance in 2026?

Absence Theories

While I think it’s sort of silly to brainstorm all the reasons students might not be coming to class, I do have at least one theory that I can quickly discuss and maybe even disprove.

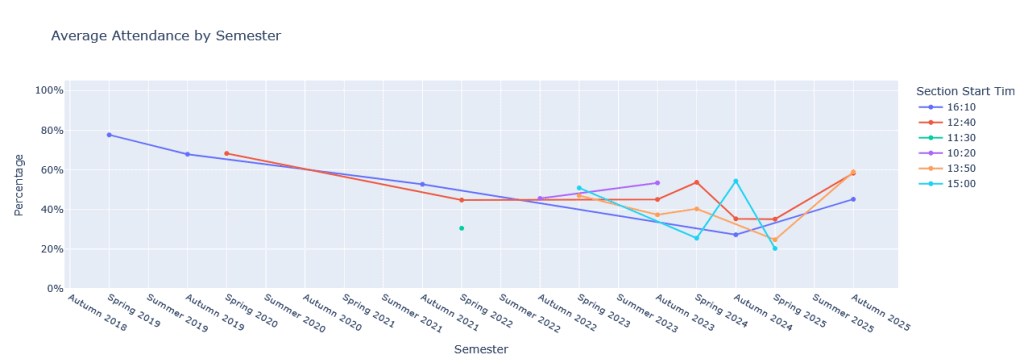

One theory I had was around time of day. For the past few semesters, my latest section has had the worst attendance. For example, last semester my 4:10 had the worst attendance average of 45%. In the previous spring, I had a 3:00 with a whopping 20% attendance rate, the worst of any section on record. The semester before that? A 4:10 with a 27% attendance rate. The 3:00 in the semester before that? A 26% attendance rate.

Of course, I thought to plot this just to be sure. Here’s the same graph from above but split by section time:

The trend generally seems to hold that the last section I teach for the day is the section that students attend the least. That trend even holds back in autumn 2023 where I had a 1:50 with the lowest attendance rate at 37%. The first time I see that trend broken is spring 2023 where the 3:00 slightly outperforms the 1:50. Then, in spring 2022, the 12:40 massively outperforms the 11:30.

Funnily enough, my 4:10 sections before the pandemic have some of the best attendance numbers ever. So, perhaps it has less to do with time of day and more to do with sequencing. Maybe I’m more burnt out and less engaging by the third session. Though, it’s hard to say.

I’m also noticing that the 3:00 is the biggest wildcard. In two semesters, it was my top performing section. In two other semesters, it was my worst performing section. That’s different from the 4:10, which is very consistently at the bottom. Meanwhile, my 1:50s and 12:40s are often comparable, with the 12:40s often slightly ahead by 5-10% on average.

Of note, I’ve only had one 11:30 that had horrible attendance. I’ve also had two 10:20s with good attendance. It was my best section in autumn 2023. Part of me wants to plot the average attendance by time, but I can lazily compute a rough version from the existing chart. Here’s that data:

- 10:20: 49.5%

- 11:30: 30%

- 12:40: 48.5%

- 1:50: 41.6%

- 3:00: 37.75%

- 4:10: 54.4%

This makes 4:10 look like the best section, but I don’t really have any data points from before the pandemic to really compare this to. If you factor out any data before the pandemic, the 4:10 average drops to 42%.

With that said, I don’t think there’s much evidence to show that time of day matters. I’ll have to keep an open mind with my 4:10 section going forward because I previously had it in my mind that no one was going to attend.

I suppose I could have just examined this theory for myself by looking at the research because at least one study shows that time of day doesn’t matter for student performance (though, it says nothing about attendance). Perhaps it was just me after all.

The Carrot or the Stick

Assuming I’m the reason attendance has dropped off (despite some evidence for some systemic reasons like COVID and AI), I’m interested in trying new ways to improve attendance. With that said, there are basically two ways to go about motivating students to attend class: the carrot and the stick.

I’ve mentioned before that I much prefer to motivate students with the carrot rather than the stick. I don’t care for policies that punish students for not showing up to class, and I don’t believe I have the power to get students to care about attending. They have to motivate themselves to show up.

Therefore, I need to find some way to encourage students to come to class. Given some of the feedback I’ve received in the last few semesters, I think I know where to start. Students seem to crave structure, and they explicitly tell me that they want more structure in the labs.

I’ve spoken at length about how I think too much structure stifles learning, but I think there are ways that I can introduce a little bit of structure to get students engaged. What I’m going to try in this upcoming semester is offer the carrot in the form of peer instruction at the beginning of each lab.

Introducing Peer Instruction

Peer instruction, for the uninitiated, is basically a clicker question. In other words, you present some multiple choice question, and you ask students to figure out the answer.

The trick with peer instruction is that you actually present the same question twice. However, the first time, you make students figure out the answer silently. Then, you ask them to debate the answer once they’ve locked one in. Afterwards, you prompt them to answer the question again before viewing the results. If all goes well, you move on. If the class struggles, you take some time to explain the concept better.

I’ve probably talked about peer instruction in other places on this site, but ever since becoming a lecturer, I haven’t really done it. I used to do it quite a bit in a previous class I taught, but I hadn’t gotten around to doing it in my current class.

Well, I had an epiphany: maybe I could start doing one of these peer instruction questions at the beginning of every lab. Looking back, this was probably implicitly inspired by a student I had last semester who would ask me a fun question at the beginning of every class. Often, I would go home and present the same question to my wife because I found it so amusing.

Anyway, I know it’s an extremely affective teaching tool, and I think it’ll get students engaged right at the beginning of each lab. If I’m right about that, then I should end up with better attendance this time around. Of course, only time will tell. I will say that there was at least one study that showed peer instruction had no effect on attendance, so I may be wasting my time.

On the plus side, if attendance doesn’t improve, I think we’ll see an interesting bimodal distribution in grades. There will be a cohort of folks who come to class and do really well and cohort that struggles significantly, especially since I’m back to paper exams this semester (more on that in the coming weeks).

Anyway, I wanted to mention that I was trying something new this semester. We’ll see how it goes! In the meantime, if you enjoyed this article, there is plenty more like it below:

- Why I Don’t Record My Lectures

- The Problem With Assessing Instructor Difficulty

- Democratic Synthesis: Taking Think-Pair-Share to the Next Level

- Top Reasons Why You Don’t Need to Take Attendance (And Why I Do It Anyway)

Likewise, you can consider providing bit more support by checking out my list of ways to grow the site. Otherwise, thanks for taking the time to check out my work!

I’m sneaking this little note down here because I have some deep cognitive dissonance around the topic of attendance.

After all, I abhor office work. Hell, I wrote an entire series about that. You will never convince me that an office can foster any kind of community, growth, or joy. If I ever found myself back in industry, it would have to be a remote job.

Yet, I believe learning has to happen in a communal setting. I deeply dread a future where education becomes more isolating as we turn to supposed personalized learning tools driven by AI. See this nice Internet of Bugs video for what I mean.

So, I’m not sure how to reconcile those two ideas right now. On one hand, I shouldn’t have to come to the office to work. On the other hand, I expect students to come to the classroom to learn. Maybe they see the classroom in the same way that I see the office, and maybe they see my attempts to make the classroom more welcoming in the same way that I see all the corporate cringe on LinkedIn.

Yet, I can’t really shake this feeling that learning environments and workplaces are two distinct categories. The former is about personal (and communal) growth while the latter is more transactional (i.e., your labor in exchange for a paycheck).

I suppose I’ve answered that question for myself by abandoning industry for academia. At least as a lecturer, I feel like I’m positively contributing to the future of society. I can’t say the same for what most folks are doing in tech.

I’ve never done this before, but I’m going to sneak a second note in here around the phrase in bold: they have to motivate themselves to show up.

For the record, I put that phrase in bold because I think it’s significant. I can understand not being motivated to show up to class. In fact, I think it’s perfectly reasonable to skip if there’s no value in it to you. However, I do think showing up to class is incredibly low stakes. It’s like putting your cart away at the grocery store. You don’t have to do it, and there’s literally no incentive for doing so. But, your willingness to return your cart anyway says a lot about your willingness to show up when the stakes rise.

Perhaps I’m making a bit of a stretch, but I think this commentary is timely. Right now, ICE is out there terrorizing our communities. As someone who has been agitating city councils to not cooperate with ICE for nearly a year, I have grown increasingly frustrated with our elected officials who seem to be too cowardly to show up and put in the work. They’re seemingly frozen in fear when this moment demands that people show up. They worry about right-wing resistance groups and funding cuts—things that are going to happen no matter what.

With one city council in particular, we met a council member who seemingly wanted to aid us in putting together a noncooperation agreement. After all, we already helped one of those agreements over the finish line in another part of the city. Unfortunately, over time, they asked us to wait because elections were happening. Elections seemingly went their way, but they began dodging us at meetings. Now, at the wake of the murder of Renee Good, they’ve completely backed down from the idea at all, citing many of the fears I mentioned before.

But if these folks won’t show up for their communities, who will? It’s moments like these where I feel like I’m surrounded by people with an unwillingness to do the bare minimum. Because if you can’t show up when the stakes are low, how can we trust you to show up when things get serious?

Recent Teach Posts

I'm being told there is an AI tool that can take the exam for students. It looks like online exams might be cooked.

I am going to kick off the new year with a bit of a bummer by talking about how my 7th year of teaching has been going (spoiler: it's not great).