If you’ve been following me for any amount of time, you know that I regularly publish Python code snippets for everyday problems. Well, I figured I’d finally aggregate all those responses in one massive article with links to all those resources.

Table of Contents

- Code Snippet Repository

- Everyday Problems

- Share Your Own Problems

Code Snippet Repository

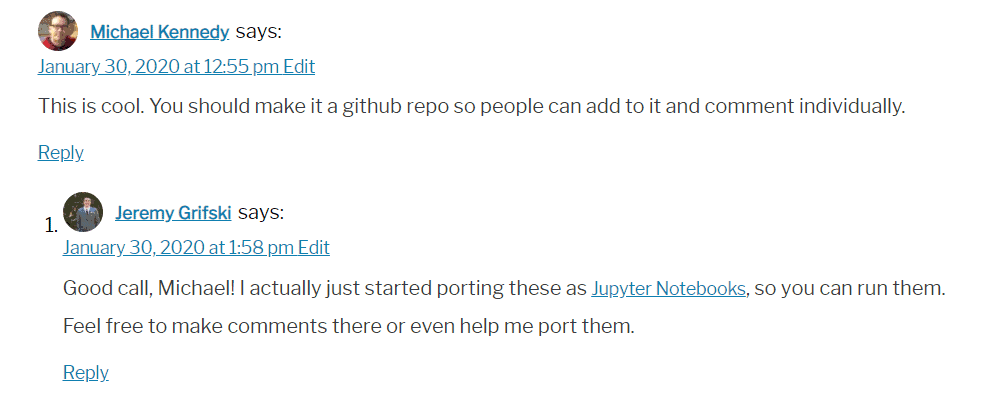

Throughout this article, you’ll find a whole host of Python code snippets. Each of these code snippets are extracted from the How to Python series. Naturally, there has been a bit of a push to create a GitHub repo for all of these snippets:

for all of these snippets:

As a result, I decided to create a repo for all of theses snippets. When you visit, you’ll find a table of articles in the README with links to loads of resources including Jupyter notebooks, #RenegadePython challenge tweets, and YouTube videos.

challenge tweets, and YouTube videos.

Personally, it’s too much for me to maintain, but I welcome you to help it grow. In the meantime, I’ll continue to update this article. Otherwise, let’s get to the list!

Everyday Problems

In this section, we’ll take a look at various common scenarios that arise and how to solve them with Python code. Specifically, I’ll share a brief explanation of the problem with a list of Python code solutions. Then, I’ll link all the resources I have.

To help you navigate this article, I’ve created separate sections for each type of problem you might find yourself tackling. For instance, I’ve put together a section on strings and a section on lists. In addition, I’ve sorted those sections alphabetically. Within each section, I’ve sorted the problems by perceived complexity. In other words, problems that I believe are more straightforward come first.

Hope that helps keep things organized for you!

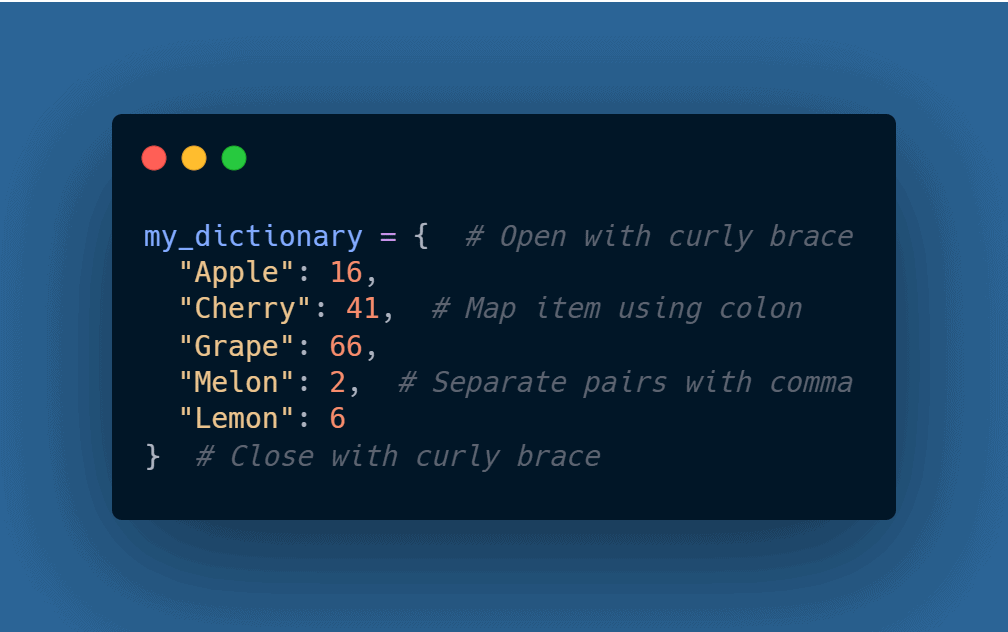

Dictionaries (17 Snippets)

One of favorite data structures in Python is the dictionary which maps pairs of items. For example, we might use a dictionary to count the number of words that appear in this article. Each key in the dictionary would be a unique word in this article. Then, each word would be mapped to its count. As you can probably imagine, this kind of structure is very useful, but it comes with its quirks. Let’s take a look at a few!

Merging Two Dictionaries

In this collection, we talk a lot about handling data structures like lists and dictionaries. Well, this one is no different. In particular, we’re looking at merging two dictionaries. Of course, combining two dictionaries comes with risks. For example, what if there are duplicate keys? Luckily, we have solutions for that:

yusuke_power = {"Yusuke Urameshi": "Spirit Gun"}

hiei_power = {"Hiei": "Jagan Eye"}

powers = dict()

# Brute force

for dictionary in (yusuke_power, hiei_power):

for key, value in dictionary.items():

powers[key] = value

# Dictionary Comprehension

powers = {key: value for d in (yusuke_power, hiei_power) for key, value in d.items()}

# Copy and update

powers = yusuke_power.copy()

powers.update(hiei_power)

# Dictionary unpacking (Python 3.5+)

powers = {**yusuke_power, **hiei_power}

# Backwards compatible function for any number of dicts

def merge_dicts(*dicts: dict):

merged_dict = dict()

for dictionary in dicts:

merge_dict.update(dictionary)

return merged_dict

# Dictionary union operator (Python 3.9+ maybe?)

powers = yusuke_power | hiei_power

If you’re interested, I have an article which covers this exact topic called “How to Merge Two Dictionaries in Python” which features four solutions as well performance metrics.

Inverting a Dictionary

Sometimes when we have a dictionary, we want to be able to flip its keys and values. Of course, there are concerns like “how do we deal with duplicate values?” and “what if the values aren’t hashable?” That said, in the simple case, there are a few solutions:

my_dict = {

'Izuku Midoriya': 'One for All',

'Katsuki Bakugo': 'Explosion',

'All Might': 'One for All',

'Ochaco Uraraka': 'Zero Gravity'

}

# Use to invert dictionaries that have unique values

my_inverted_dict = dict(map(reversed, my_dict.items()))

# Use to invert dictionaries that have unique values

my_inverted_dict = {value: key for key, value in my_dict.items()}

# Use to invert dictionaries that have non-unique values

from collections import defaultdict

my_inverted_dict = defaultdict(list)

{my_inverted_dict[v].append(k) for k, v in my_dict.items()}

# Use to invert dictionaries that have non-unique values

my_inverted_dict = dict()

for key, value in my_dict.items():

my_inverted_dict.setdefault(value, list()).append(key)

# Use to invert dictionaries that have lists of values

my_dict = {value: key for key in my_inverted_dict for value in my_inverted_dict[key]}

For more explanation, check out my article titled “How to Invert a Dictionary in Python.” It includes a breakdown of each solution, their performance metrics, and when they’re applicable. Likewise, I have a YouTube video which covers the same topic.

which covers the same topic.

Performing a Reverse Dictionary Lookup

Earlier we talked about reversing a dictionary which is fine in some circumstances. Of course, if our dictionary is enormous, it might not make sense to outright flip the dict. Instead, we can lookup a key based on a value:

my_dict = {"color": "red", "width": 17, "height": 19}

value_to_find = "red"

# Brute force solution (fastest) -- single key

for key, value in my_dict.items():

if value == value_to_find:

print(f'{key}: {value}')

break

# Brute force solution -- multiple keys

for key, value in my_dict.items():

if value == value_to_find:

print(f'{key}: {value}')

# Generator expression -- single key

key = next(key for key, value in my_dict.items() if value == value_to_find)

print(f'{key}: {value_to_find}')

# Generator expression -- multiple keys

exp = (key for key, value in my_dict.items() if value == value_to_find)

for key in exp:

print(f'{key}: {value}')

# Inverse dictionary solution -- single key

my_inverted_dict = {value: key for key, value in my_dict.items()}

print(f'{my_inverted_dict[value_to_find]}: {value_to_find}')

# Inverse dictionary solution (slowest) -- multiple keys

my_inverted_dict = dict()

for key, value in my_dict.items():

my_inverted_dict.setdefault(value, list()).append(key)

print(f'{my_inverted_dict[value_to_find]}: {value_to_find}')

If this seems helpful, you can check out the source article titled “How to Perform a Reverse Dictionary Lookup in Python“. One of the things I loved about writing this article was learning about generator expressions. If you’re seeing them for the first time, you might want to check it out.

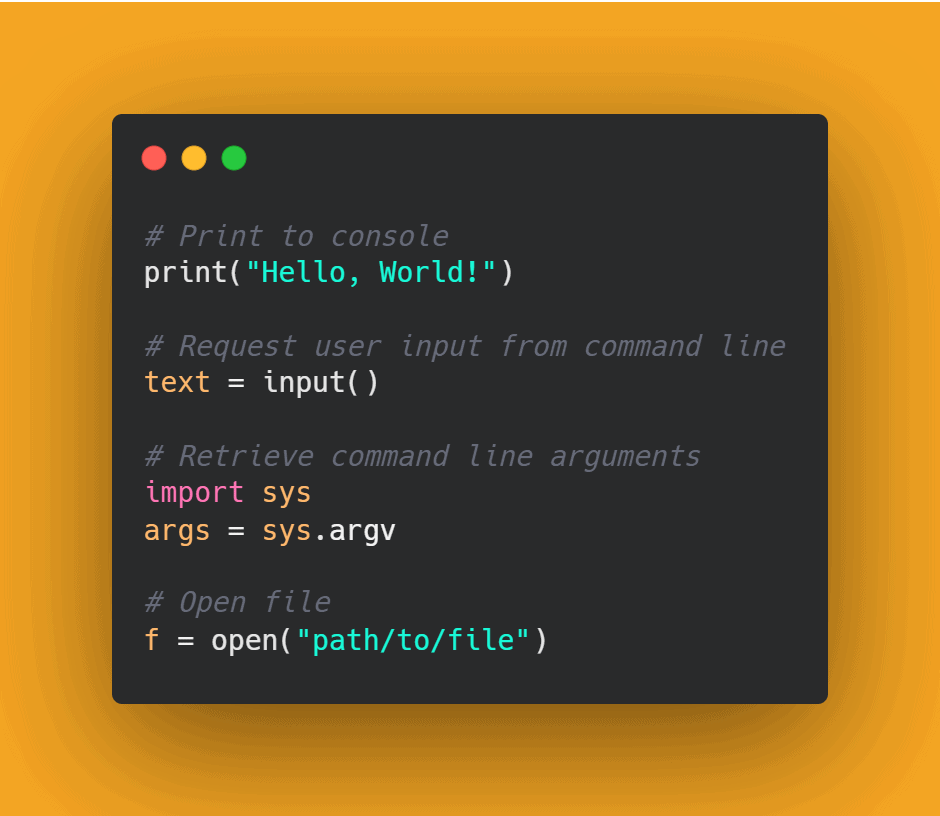

Input/Output (12 Snippets)

In software development, Input/Output (I/O) refers to any time a program reaches for data that is external to the source code. Common examples of I/O include reading from and writing to databases, files, and command line interfaces. Naturally, Python does a great job of making I/O accessible, but there are still challenges. Here are a few!

Printing on the Same Line

Along a similar line as formatting strings, sometimes you just need to print on the same line in Python. As the print command is currently designed, it automatically applies a newline to the end of your string. Luckily, there are a few ways around that:

# Python 2 only

print "Live PD",

# Backwards compatible (also fastest)

import sys

sys.stdout.write("Breaking Bad")

# Python 3 only

print("Mob Psycho 100", end="")

As always, if you plan to use any of these solutions, check out the article titled “How to Print on the Same Line in Python” for additional use cases and caveats.

Making a Python Script Shortcut

Sometimes when you create a script, you want to be able to run it conveniently at the click of a button. Fortunately, there are several ways to do that.

First, we can create a Windows shortcut with the following settings:

\path\to\trc-image-titler.py -o \path\to\output

Likewise, we can also create a batch file with the following code:

@echo off \path\to\trc-image-titler.py -o \path\to\output

Finally, we can create a bash script with the following code:

#!/bin/sh python /path/to/trc-image-titler.py -o /path/to/output

If you’re looking for more explanation, check out the article titled “How to Make a Python Script Shortcut with Arguments.”

Checking if a File Exists

One of the amazing perks of Python is how easy it is to manage files. Unlike Java, Python has a built-in syntax for file reading and writing. As a result, checking if a file exists is a rather brief task:

# Brute force with a try-except block (Python 3+)

try:

with open('/path/to/file', 'r') as fh:

pass

except FileNotFoundError:

pass

# Leverage the OS package (possible race condition)

import os

exists = os.path.isfile('/path/to/file')

# Wrap the path in an object for enhanced functionality

from pathlib import Path

config = Path('/path/to/file')

if config.is_file():

pass

As always, you can learn more about these solutions in my article titled “How to Check if a File Exists in Python” which features three solutions and performances metrics.

Parsing a Spreadsheet

One of the more interesting use cases for Python is data science. Unfortunately, however, that means handling a lot of raw data in various formats like text files and spreadsheets. Luckily, Python has plenty of built-in utilities for reading different file formats. For example, we can parse a spreadsheet with ease:

# Brute force solution

csv_mapping_list = []

with open("/path/to/data.csv") as my_data:

line_count = 0

for line in my_data:

row_list = [val.strip() for val in line.split(",")]

if line_count == 0:

header = row_list

else:

row_dict = {key: value for key, value in zip(header, row_list)}

csv_mapping_list.append(row_dict)

line_count += 1

# CSV reader solution

import csv

csv_mapping_list = []

with open("/path/to/data.csv") as my_data:

csv_reader = csv.reader(my_data, delimiter=",")

line_count = 0

for line in csv_reader:

if line_count == 0:

header = line

else:

row_dict = {key: value for key, value in zip(header, line)}

csv_mapping_list.append(row_dict)

line_count += 1

# CSV DictReader solution

import csv

with open("/path/to/dict.csv") as my_data:

csv_mapping_list = list(csv.DictReader(my_data))

In this case, we try to get our output in a list of dictionaries. If you want to know more about how this works, check out the complete article titled “How to Parse a Spreadsheet in Python.”

Lists (43 Snippets)

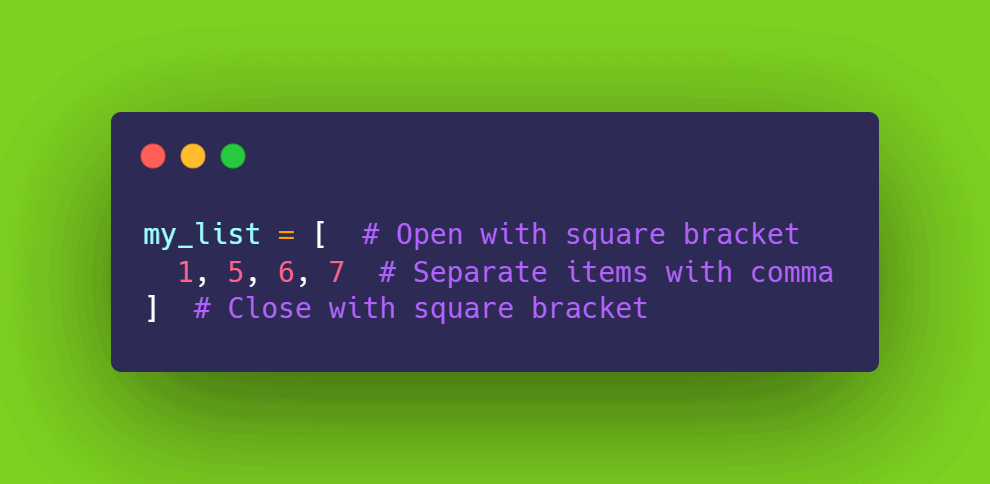

When it comes to data structures, none are more ubiquitous than the list. In Python, in particular, the list is a dynamic array which uses zero-based indexing. In other words, we can added and remove items without really caring too much about what it looks like under the hood. That makes lists really intuitive. Of course, like other data structures in this list (no pun intended), lists come with their own challenges. Let’s take a look!

Adding An Item to a List

As this collection expanded, I grew interested in Python fundamentals. In other words, what are some things that absolute beginners might want to do, and how many different ways are there to do those things? One of those things was adding an item to a list.

Luckily, Python has a ton of ways of adding items to lists. For example, there’s the popular append() method. However, there are tons of other options. Here are five:

# Statically defined list my_list = [2, 5, 6] # Appending using slice assignment my_list[len(my_list):] = [5] # [2, 5, 6, 5] # Appending using append() my_list.append(9) # [2, 5, 6, 5, 9] # Appending using extend() my_list.extend([-4]) # [2, 5, 6, 5, 9, -4] # Appending using insert() my_list.insert(len(my_list), 3) # [2, 5, 6, 5, 9, -4, 3]

Naturally, I’ve written all about these solutions in more in my article titled “How to Add an Item to a List in Python.”

Retrieving the Last Item of a List

Since we’re on the topic of lists, lets talk about getting the last item of a list. In most languages, this involves some convoluted mathematical expression involving the length of the list. What if I told you there is are several more interesting solutions in Python?

my_list = ['red', 'blue', 'green'] # Get the last item with brute force using len last_item = my_list[len(my_list) - 1] # Remove the last item from the list using pop last_item = my_list.pop() # Get the last item using negative indices *preferred & quickest method* last_item = my_list[-1] # Get the last item using iterable unpacking *_, last_item = my_list

As always, you can learn more about these solutions from my article titled “How to Get the Last Item of a List in Python” which features a challenge, performance metrics, and a YouTube video .

.

Checking if a List Is Empty

If you come from a statically typed language like Java or C, you might be bothered by the lack of static types in Python. Sure, not knowing the type of a variable can sometimes be frustrating, but there are perks as well. For instance, we can check if a list is empty by its type flexibility—among other methods:

my_list = list()

# Check if a list is empty by its length

if len(my_list) == 0:

pass # the list is empty

# Check if a list is empty by direct comparison (only works for lists)

if my_list == []:

pass # the list is empty

# Check if a list is empty by its type flexibility **preferred method**

if not my_list:

pass # the list is empty

If you’d like to learn more about these three solutions, check out my article titled “How to Check if a List in Empty in Python.” If you’re in a pinch, check out my YouTube video which covers the same topic .

.

Cloning a List

One of my favorite subjects in programming is copying data types. After all, it’s never easy in this reference-based world we live, and that’s true for Python as well. Luckily, if we want to copy a list, there are a few ways to do it:

my_list = [27, 13, -11, 60, 39, 15] # Clone a list by brute force my_duplicate_list = [item for item in my_list] # Clone a list with a slice my_duplicate_list = my_list[:] # Clone a list with the list constructor my_duplicate_list = list(my_list) # Clone a list with the copy function (Python 3.3+) my_duplicate_list = my_list.copy() # preferred method # Clone a list with the copy package import copy my_duplicate_list = copy.copy(my_list) my_deep_duplicate_list = copy.deepcopy(my_list) # Clone a list with multiplication? my_duplicate_list = my_list * 1 # do not do this

When it comes to cloning, it’s important to be aware of the difference between shallow and deep copies. Luckily, I have an article covering that topic.

Finally, you can find out more about the solutions listed above in my article titled “How to Clone a List in Python.” In addition, you might find value in my related YouTube video titled “7 Ways to Copy a List in Python Featuring The Pittsburgh Penguins .”

.”

Writing a List Comprehension

One of my favorite Python topics to chat about is list comprehensions. As someone who grew up on languages like Java, C/C++, and C#, I had never seen anything quite like a list comprehension until I played with Python. Now, I’m positively obsessed with them. As a result, I put together an entire list of examples:

my_list = [2, 5, -4, 6] # Duplicate a 1D list of constants [item for item in my_list] # Duplicate and scale a 1D list of constants [2 * item for item in my_list] # Duplicate and filter out non-negatives from 1D list of constants [item for item in my_list if item < 0] # Duplicate, filter, and scale a 1D list of constants [2 * item for item in my_list if item < 0] # Generate all possible pairs from two lists [(a, b) for a in (1, 3, 5) for b in (2, 4, 6)]

my_list = [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

# Duplicate a 2D list

[[item for item in sub_list] for sub_list in my_list]

# Duplicate an n-dimensional list

def deep_copy(to_copy):

if type(to_copy) is list:

return [deep_copy(item) for item in to_copy]

else:

return to_copy

As always, you can find a more formal explanation of all this code in my article titled “How to Write a List Comprehension in Python.” As an added bonus, I have a YouTube video which shares several examples of list comprehensions .

.

Summing Elements of Two Lists

Let’s say you have two lists, and you want to merge them together into a single list by element. In other words, you want to add the first element of the first list to the first element of the second list and store the result in a new list. Well, there are several ways to do that:

ethernet_devices = [1, [7], [2], [8374163], [84302738]]

usb_devices = [1, [7], [1], [2314567], [0]]

# The long way

all_devices = [

ethernet_devices[0] + usb_devices[0],

ethernet_devices[1] + usb_devices[1],

ethernet_devices[2] + usb_devices[2],

ethernet_devices[3] + usb_devices[3],

ethernet_devices[4] + usb_devices[4]

]

# Some comprehension magic

all_devices = [x + y for x, y in zip(ethernet_devices, usb_devices)]

# Let's use maps

import operator

all_devices = list(map(operator.add, ethernet_devices, usb_devices))

# We can't forget our favorite computation library

import numpy as np

all_devices = np.add(ethernet_devices, usb_devices)

If you’d like a deeper explanation, check out my article titled “How to Sum Elements of Two Lists in Python” which even includes a fun challenge. Likewise, you might get some value out of my YouTube video on the same topic .

.

Converting Two Lists Into a Dictionary

Previously, we talked about summing two lists in Python. As it turns out, there’s a lot we can do with two lists. For example, we could try mapping one onto the other to create a dictionary.

As with many of these problems, there are a few concerns. For instance, what if the two lists aren’t the same size? Likewise, what if the keys aren’t unique or hashable? That said, in the simple case, there are some straightforward solutions:

column_names = ['id', 'color', 'style']

column_values = [1, 'red', 'bold']

# Convert two lists into a dictionary with zip and the dict constructor

name_to_value_dict = dict(zip(column_names, column_values))

# Convert two lists into a dictionary with a dictionary comprehension

name_to_value_dict = {key:value for key, value in zip(column_names, column_values)}

# Convert two lists into a dictionary with a loop

name_value_tuples = zip(column_names, column_values)

name_to_value_dict = {}

for key, value in name_value_tuples:

if key in name_to_value_dict:

pass # Insert logic for handling duplicate keys

else:

name_to_value_dict[key] = value

Once again, you can find an explanation for each of these solutions and more in my article titled “How to Convert Two Lists Into a Dictionary in Python.” If you are a visual person, you might prefer my YouTube video which covers mapping lists to dictionaries as well.

as well.

Sorting a List of Strings

Sorting is a common task that you’re expected to know how to implement in Computer Science. Despite the intense focus on sorting algorithms in most curriculum, no one really tells you how complicated sorting can actually get. For instance, sorting numbers is straightforward, but what about sorting strings? How do we decide a proper ordering? Fortunately, there are a lot of options in Python:

my_list = ["leaf", "cherry", "fish"]

# Brute force method using bubble sort

my_list = ["leaf", "cherry", "fish"]

size = len(my_list)

for i in range(size):

for j in range(size):

if my_list[i] < my_list[j]:

temp = my_list[i]

my_list[i] = my_list[j]

my_list[j] = temp

# Generic list sort *fastest*

my_list.sort()

# Casefold list sort

my_list.sort(key=str.casefold)

# Generic list sorted

my_list = sorted(my_list)

# Custom list sort using casefold (>= Python 3.3)

my_list = sorted(my_list, key=str.casefold)

# Custom list sort using current locale

import locale

from functools import cmp_to_key

my_list = sorted(my_list, key=cmp_to_key(locale.strcoll))

# Custom reverse list sort using casefold (>= Python 3.3)

my_list = sorted(my_list, key=str.casefold, reverse=True)

If you’re curious about how some of these solutions work, or you just want to know what some of the potential risks are, check out my article titled “How to Sort a List of Strings in Python.”

Sorting a List of Dictionaries

Once you have a list of dictionaries, you might want to organize them in some specific order. For example, if the dictionaries have a key for date, we can try sorting them in chronological order. Luckily, sorting is another relatively painless task:

csv_mapping_list = [

{

"Name": "Jeremy",

"Age": 25,

"Favorite Color": "Blue"

},

{

"Name": "Ally",

"Age": 41,

"Favorite Color": "Magenta"

},

{

"Name": "Jasmine",

"Age": 29,

"Favorite Color": "Aqua"

}

]

# Custom sorting

size = len(csv_mapping_list)

for i in range(size):

min_index = i

for j in range(i + 1, size):

if csv_mapping_list[min_index]["Age"] > csv_mapping_list[j]["Age"]:

min_index = j

csv_mapping_list[i], csv_mapping_list[min_index] = csv_mapping_list[min_index], csv_mapping_list[i]

# List sorting function

csv_mapping_list.sort(key=lambda item: item.get("Age"))

# List sorting using itemgetter

from operator import itemgetter

f = itemgetter('Name')

csv_mapping_list.sort(key=f)

# Iterable sorted function

csv_mapping_list = sorted(csv_mapping_list, key=lambda item: item.get("Age"))

All these solutions and more outlined in my article titled “How to Sort a List of Dictionaries in Python.”

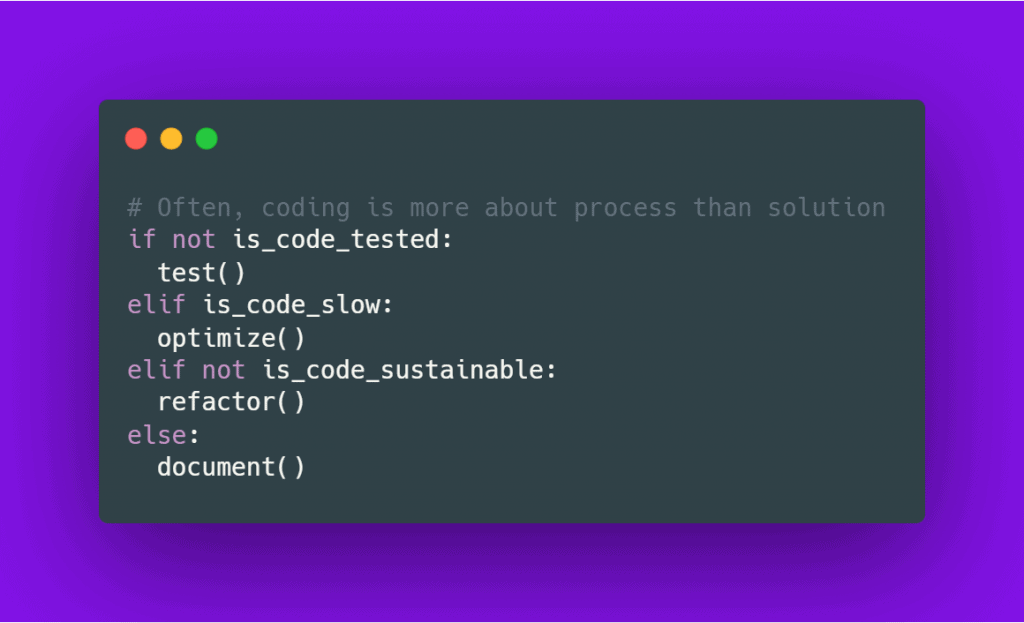

Meta (6 Snippets)

Sometimes coding is less about writing code and more about making sense of the code. As a result, I felt it made sense to create a section dedicated to solving Python development challenges like testing. Check it out!

Commenting Code

When it comes to writing code, I’m often of the opinion that code should be as readable as possible without comments. That said, comments have value, so it’s important to know how to write them. Luckily, Python supports three main options:

# Here is an inline comment in Python # Here # is # a # multiline # comment # in # Python """ Here is another multiline comment in Python. This is sometimes interpreted as a docstring, so be careful where you put these. """

If you’re interested in exploring these options a bit deeper, check out my article titled “How to Comment Code in Python.”

Testing Performance

Sometimes you just want to compare a couple chunks of code. Luckily, Python has a few straightforward options including two libraries, timeit and cProfile. Take a look:

# Brute force solution

import datetime

start_time = datetime.datetime.now()

[(a, b) for a in (1, 3, 5) for b in (2, 4, 6)] # example snippet

end_time = datetime.datetime.now()

print end_time - start_time

# timeit solution

import timeit

min(timeit.repeat("[(a, b) for a in (1, 3, 5) for b in (2, 4, 6)]"))

# cProfile solution

import cProfile

cProfile.run("[(a, b) for a in (1, 3, 5) for b in (2, 4, 6)]")

If you’ve read any of the articles in the How to Python series, then you know how often I use the timeit library to measure performance. That said, it’s nice to know that there are different options for different scenarios.

As always, if you want to learn more about testing, check the article titled “How to Performance Test Python Code.”

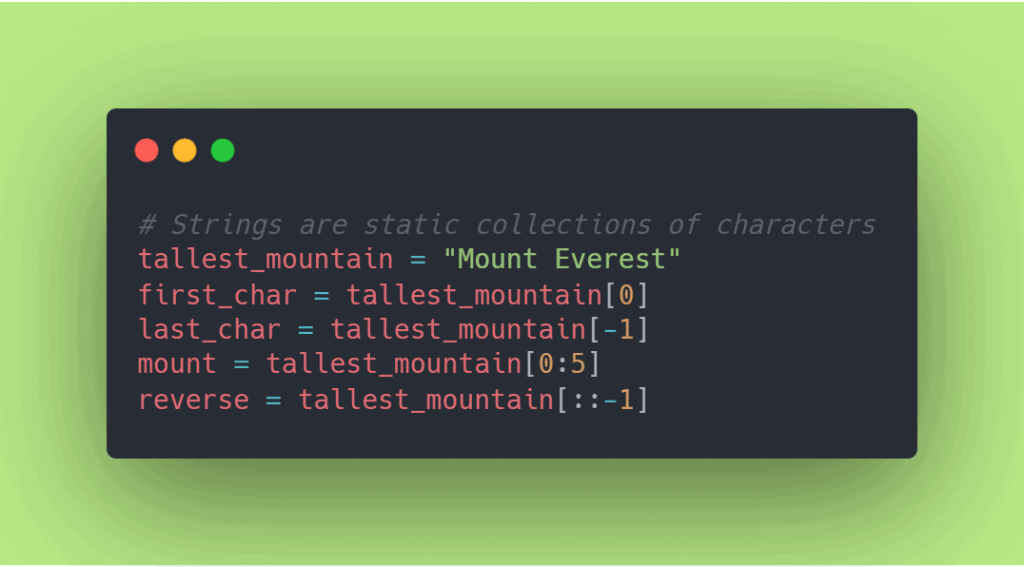

Strings (22 Snippets)

In the world of programming, strings are an abstraction created to represent a collection of characters. Naturally, they can be used to store text data like names and email addresses. Unfortunately, that means strings are extremely complex, so there are a ton of string related problems. In this section, we’ll look at a handful of those problems.

Comparing Strings

Perhaps one of the most common questions people ask after creating a few strings is how to compare them. In Python, there are a lot of different ways to compare strings which depend on your needs. For example, do we want to know if two strings are equal? Or, do we just need to know how they compare alphabetically?

For each scenario, there are different tools we can use. Here’s a quick list of options:

penguins_87 = "Crosby"

penguins_71 = "Malkin"

penguins_59 = "Guentzel"

# Brute force comparison (equality only)

is_same_player = len(penguins_87) == len(penguins_59)

if is_same_player:

for a, b in zip(penguins_87, penguins_59):

if a != b:

is_same_player = False

break

# Direct comparison

penguins_87 == penguins_59 # False

penguins_87 > penguins_59 # False

penguins_71 <= penguins_71 # True

# Identity checking

penguins_87 is penguins_87 # True

penguins_71 is penguins_87 # False

In these examples, we demonstrate a few different types of comparison. For example, we can check for equality using the == operator. Of course, if we only need to check alphabetical ordering, we can opt for one of the relational operators like greater than (>). Likewise, Python has the is operator for checking identity.

If you’d like to learn more about these different operators, check out this article titled “How to Compare Strings in Python.” Of course, if you’d prefer, you’re welcome to check out this YouTube video instead .

.

Checking for Substrings

One thing I find myself searching more often than I should is the way to check if a string contains a substring in Python. Unlike most programming languages, Python leverages a nice keyword for this problem. Of course, there are also method-based solutions as well:

addresses = [

"123 Elm Street",

"531 Oak Street",

"678 Maple Street"

]

street = "Elm Street"

# Brute force (don't do this)

for address in addresses:

address_length = len(address)

street_length = len(street)

for index in range(address_length - street_length + 1):

substring = address[index:street_length + index]

if substring == street:

print(address)

# The index method

for address in addresses:

try:

address.index(street)

print(address)

except ValueError:

pass

# The find method

for address in addresses:

if address.find(street) >= 0:

print(address)

# The in keyword (fastest/preferred)

for address in addresses:

if street in address:

print(address)

If you’re like me and forget about the in keyword, you might want to bookmark the “How to Check if a String Contains a Substring” article.

Formatting a String

Whether we like to admit it or not, we often find ourselves burying print statements throughout our code for quick debugging purposes. After all, a well placed print statement can save you a lot of time. Unfortunately, it’s not always easy or convenient to actually display what we want. Luckily, Python has a lot of formatting options:

name = "Jeremy"

age = 25

# String formatting using concatenation

print("My name is " + name + ", and I am " + str(age) + " years old.")

# String formatting using multiple prints

print("My name is ", end="")

print(name, end="")

print(", and I am ", end="")

print(age, end="")

print(" years old.")

# String formatting using join

print(''.join(["My name is ", name, ", and I am ", str(age), " years old"]))

# String formatting using modulus operator

print("My name is %s, and I am %d years old." % (name, age))

# String formatting using format function with ordered parameters

print("My name is {}, and I am {} years old".format(name, age))

# String formatting using format function with named parameters

print("My name is {n}, and I am {a} years old".format(a=age, n=name))

# String formatting using f-Strings (Python 3.6+)

print(f"My name is {name}, and I am {age} years old")

Keep in mind that these solutions don’t have to be used with print statements. In other words, feel free to use solutions like f-strings wherever you need them.

As always, you can find an explanation of all these solutions and more in my article titled “How to Format a String in Python.” If you’d rather see these snippets in action, check out my YouTube video titled “6 Ways to Format a String in Python Featuring My Cat .”

.”

Converting a String to Lowercase

In the process of formatting or comparing a string, we may find that one way to reduce a strings complexity is to convert all the characters to lowercase. For instance, we might do this when we want check if two strings match, but we don’t care if the casing is the same. Here are a few ways to do that:

from string import ascii_lowercase, ascii_uppercase

hero = "All Might"

# Brute force using concatenation

output = ""

for char in hero:

if "A" <= char <= "Z":

output += chr(ord(char) - ord('A') + ord('a'))

else:

output += char

# Brute force using join

output = []

for char in hero:

if "A" <= char <= "Z":

output.append(chr(ord(char) - ord('A') + ord('a')))

else:

output.append(char)

output = "".join(output)

# Brute force using ASCII collections

output = []

for char in hero:

if char in ascii_uppercase:

output.append(ascii_lowercase[ascii_uppercase.index(char)])

else:

output.append(char)

output = "".join(output)

# Brute force using a list comprehension

output = [ascii_lowercase[ascii_uppercase.index(char)] if char in ascii_uppercase else char for char in hero]

output = "".join(output)

# Built-in Python solution

output = hero.lower()

Like many problems in this collection, there’s an article that goes into even more depth on how to solve this problem; it’s titled “How to Convert a String to Lowercase in Python,” and it covers all these solutions and more. In addition, it includes a challenge for converting a string to title case.

Splitting a String by Whitespace

While dealing with locale and other language issues is tough, it’s also tough to handle grammar concepts like words and sentences. For instance, how would we go about breaking a string into words? One rough way to do that is to split that string by spaces. Take a look:

my_string = "Hi, fam!"

# Split that only works when there are no consecutive separators

def split_string(my_string: str, seps: list):

items = []

i = 0

while i < len(my_string):

sub = next_word_or_separator(my_string, i, seps)

if sub[0] not in seps:

items.append(sub)

i += len(sub)

return items

split_string(my_string) # ["Hi,", "fam!"]

# A more robust, albeit much slower, implementation of split

def next_word_or_separator(text: str, position: int, separators: list):

test_separator = lambda x: text[x] in separators

end_index = position

is_separator = test_separator(position)

while end_index < len(text) and is_separator == test_separator(end_index):

end_index += 1

return text[position: end_index]

def split_string(my_string: str, seps: list):

items = []

i = 0

while i < len(my_string):

sub = next_word_or_separator(my_string, i, seps)

if sub[0] not in seps:

items.append(sub)

i += len(sub)

return items

split_string(my_string) # ["Hi,", "fam!"]

# The builtin split solution **preferred**

my_string.split() # ["Hi,", "fam!"]

Clearly, the idea of string splitting is a complex subject. If you’re interested in learning more about what went into these snippets, check out the article titled “How to Split a String by Whitespace in Python.”

Share Your Own Problems

As you can see, this article and its associated series is already quite large. That said, I’d love to continue growing them. As a result, you should consider sharing some of your own problems. After all, there has be something you Google regularly. Why not share it with us?

If you have something to share, head on over to Twitter and drop it into a tweet with the hashtag #RenegadePython . If I see it, I’ll give it a share. If I have time, I might even make an article about it.

. If I see it, I’ll give it a share. If I have time, I might even make an article about it.

In the meantime, help grow this collection by hopping on my newsletter, subscribing to my YouTube channel , and/or becoming a patron

, and/or becoming a patron . In addition, you’re welcome to browse the following related articles:

. In addition, you’re welcome to browse the following related articles:

- The Controversy Behind the Walrus Operator in Python

- Rock Paper Scissors Using Modular Arithmetic

- Coolest Python Programming Language Features

Likewise, here are a few Python resources from Amazon (ad):

- Effective Python: 90 Specific Ways to Write Better Python

- Python Tricks: A Buffet of Awesome Python Features

- Python Programming: An Introduction to Computer Science

Otherwise, thanks for stopping by! I appreciate the support.

Recent Code Posts

In growing the Python concept map, I thought I'd take today to cover the concept of special methods as their called in the documentation. However, you may have heard them called magic methods or even...

Today, we're expanding our new concept series by building on the concept of an iterable. Specifically, we'll be looking at a feature of iterables called iterable unpacking. Let's get into it!